Site Search

Search within product

第741号 2022(R04).06発行

Click here for PDF version

§ Nutrient water absorption and its transfer between day and night in tomatoes

Former Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University

桝田 正治

No § Soil - No.12

堆肥の効果の現れ方と土の条件

−土の黒さが決め手−

Jcam Agri Co.

北海道支店 技術顧問

松中 照夫

Nutrient water absorption and its transfer during day and night in tomato

Former Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University

桝田 正治

Introduction

Living organisms on the earth live in a natural day-night cycle. The earth rotates around the sun once a year, but because the axis of rotation around the south and north poles is tilted 23.5 degrees from the so-called orbital plane, the length of day and night and temperature change in mid-latitude regions such as Japan, resulting in four seasons. Many plants flower and bear fruit in response to these day lengths and temperatures. In low-latitude regions near the equator, where the earth's rotation and revolution are on the same orbit, the four seasons do not occur, and day and night repeat at approximately 12-12 hours per day. In this region, there are wet and dry seasons, and many plants flower in response to the rain. The desert is home to many succulent plants, some of which store water like cacti, while others, like the baobab, store water in their trunks, shedding their leaves during the dry season and growing more leaves during the rainy season. Thus, it can be said that plants on earth have evolved by adapting to their natural environment, including light, temperature, and water.

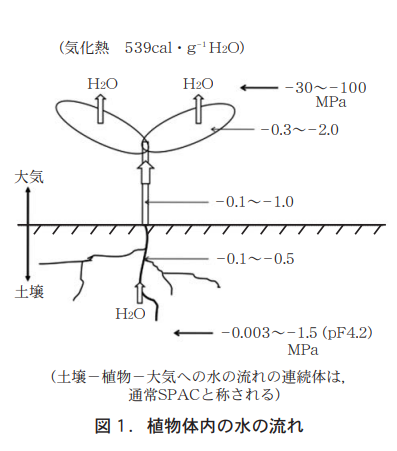

The various forms found in the above-ground part of the plant are only possible through the maintenance of the individual organism, and its survival would not be possible without the presence of roots. Roots receive photosynthetic products from the above-ground parts, and they also transfer water and nutrients to the above-ground parts. The flow of water is shown in Figure 1. Roots absorb water attracted to the soil (called water potential, the value of which is always negative) and raise the water from the stem to the leaves, where the water potential is lower. Rather than being lifted, the water is pulled up by the transpiration force generated by the water potential of the leaves. The water evaporates from the leaf and cools the leaf surface as heat of vaporization. At this time, the various nutrients dissolved in water in the form of ions are distributed to the various parts of the plant. The water flow in the plant differs greatly from day to night.

This paper is a review of how root nutrient uptake and translocation changes in response to the day-night environment of the above-ground zone, mainly based on the author's previous research, citing the literature.

2. daytime and nighttime stem and root elongation and fruit enlargement

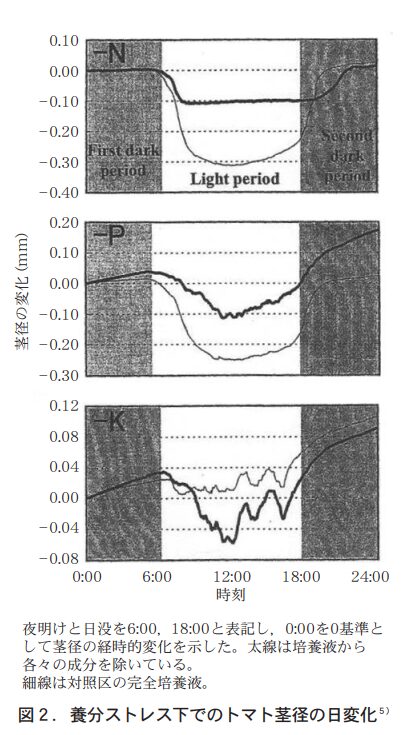

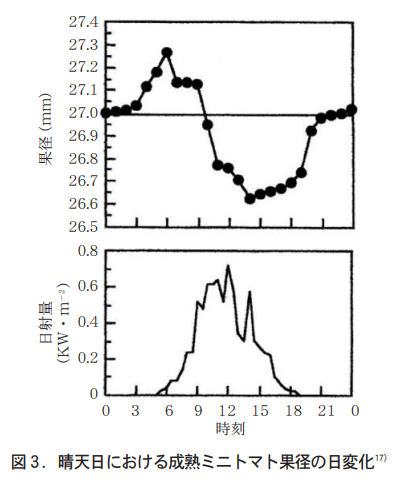

トマトの茎の伸長は,日単位で見ると昼間よりも夜間の方が大きく70〜80%は夜間に行われ25),茎の直径は昼間に縮む(図2) 。昼間に縮む現象はブドウでも端的に示されている4)。これは茎組織での水ポテンシャルが昼間に低下し細胞の膨圧が低下することによる。トマトの果径についても,昼間に減少し13時頃には最低となることが示されている(図3) 。

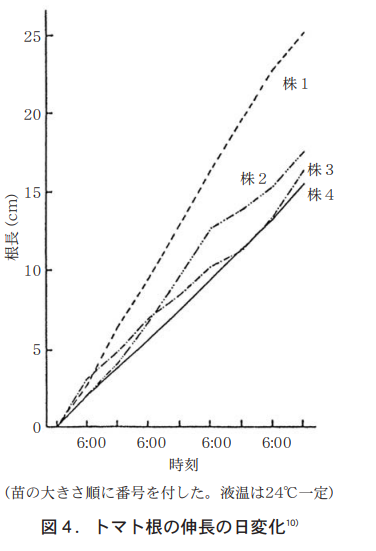

The author placed tomato seedlings on a sloping tin plate, continuously poured nutrient solution at 24°C, and measured the roots growing under the black sheet at 6:00 am and 6:00 pm.

前報の総合考察において大学入試センター試験問題を引用したように12),根は地上部から送られてくるシグナルによって水や養分の吸収に応えている。例えば,大玉トマトが第3果房まで着果したとき果実を摘果すると,12日後には根の乾物重は対照株の3割増し,培養液のNO3−N,Ca,Mgの濃度は急落する。これは摘果によって,これら5) 成分の吸収濃度(n/w,後述)が急激に増すことを意味する。しかし,PとKの濃度に変化は見られない13)。成分によって吸収の速度が異なってくる理由については今なお分かっていない。

近年,塚本ら23)は非破壊で植物生体内の物質動態を可視化できるPositronemitting Tracer Imaging System(PETIS) を用いて,トマト側枝葉に処理した11CO2の移動画像から側枝葉の果実への寄与率を求めているが,本手法は摘葉や摘果に伴う根での養分動態解析などにも適用できるものと思われ,今後大いに期待されるところである。

3. leaf and fruit water potentials during day and night

-The appearance of the fruit...

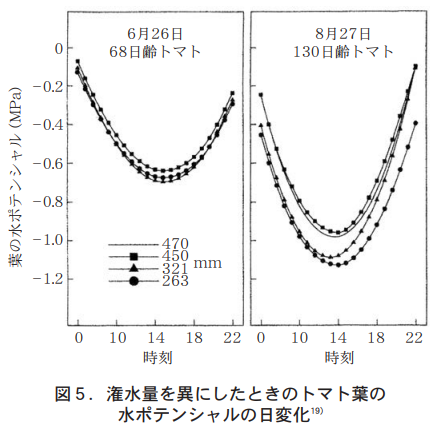

As mentioned earlier, transpiration from plant leaves decreases the water potential in the body. This creates water absorption, and water is drawn up through conduits as mass flow. Normal water potential decreases during the day and increases at night. However, even at night, the water potential is always negative and never positive. As shown in Figure 5, the water potential of tomato leaves reaches a minimum around 14:00 at -1.0 MPa and a maximum at midnight, regardless of the irrigation rate. It is widely known that fruit breakage occurs frequently, especially when rainfall occurs after drought, and techniques such as rain-fed cultivation have been widely used to prevent fruit breakage.

太田17)は,ミニトマトの裂果について調べ,早朝の5〜7時に多く発生すること,この頃に果実の横径が増すことから,裂果には圧ポテンシャルの増大による果実の膨張が関係しているとした。さらに同氏は夜間に葉での蒸散を促進すれば果実への水流入が少なくなるとの考えから,夜間に6000luxの照明を行ったところ,裂果は対照区の40%以下に抑えられたとしている。実験条件としての土耕と水耕,また普通トマトとミニトマトなどの違いを考慮したとしても,図5に示したように,葉の水ポテンシャルが最高値となる真夜中の時間帯と裂果が発生する朝方時間帯を考えるとき,両者には約6時間のタイムラグが生じていることが分かる。この6時間における果肉,果皮組織への水流入の動態が重水トレーサーなどにより明らかになれば,裂果のさらなる制御技術も生まれるであろうと期待される。

4. day/night nutrient absorption concentrations (n/w) and nutrient transfer

筆者らは,園試標準培養液においてトマトの昼夜における養分吸収濃度(n/w)を求めたところ,昼はどの成分も培養液の濃度に近い値となるが,夜は昼間の2.2倍から3.7倍となることを1984年園芸学会春季大会において発表した。同大会において,寺林らも同様な結果を報告している。ここでいう吸収濃度とは,1970年代に山崎ら24)によって提唱された概念で,広く一般に使用され野菜の培養液管理の指針とされてきた。これは,作物の吸収した成分量(n)を水量(w)で除した値で,通常me/ℓで表記される。春季に昼用〈6:00−18:00〉と夜用〈18:00−6:00〉のポットに標準培養液を入れ,同一株を移し替えること5日間,この養水分のn/w値を図6に示した。昼間のn/wは当初の培養液濃度に近い値となるが,夜間のn/wはどの成分も培養液濃度の2〜3倍で,特にPは6倍近くになることが分かる。寺林ら22)も,夏季に昼間7:00−19:00,夜間19:00−7:00として4日間株を移し替え調査した結果,Pの夜間吸収率は他の成分に比べて非常に高くなることを認めている。

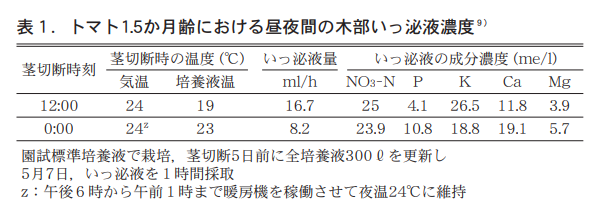

Assuming Xℓ of initial culture, Yℓ of liquid at the end, Zℓ of water surface evaporation during this period (blank area), a concentration before treatment, and b concentration after treatment, n/w is expressed as (aX-bY) / (X-Y-Z). The fact that n/w is higher at night strongly suggests that the concentration of xylem liquid transferred to the ground is also higher. Therefore, we cut stems of 1.5-month-old tomato plants at 10 cm from the ground and collected and analyzed the xylem secretions, and found that the amount of secretions at night was half that of daytime, the concentrations of NO3-N and K were higher during the daytime, and P, Ca, and Mg were higher during the nighttime. P, Ca, and Mg were found to be higher at night. In particular, K was 1.4 times higher in the daytime than in the nighttime, and P was 2.5 times higher in the nighttime than in the daytime (Table 1).

さらに,同一培養液でトマトを育て24時間にわたり1時間毎に一株ずつ茎を切除して15分間採取したいっ泌液を分析した結果,成分濃度の回帰曲線においてKは朝方から正午にかけて,Pは夕方から午後10時にかけて上昇することが明らかとなった(14)The following is a list of the most common problems with the "C" in the "C" column.

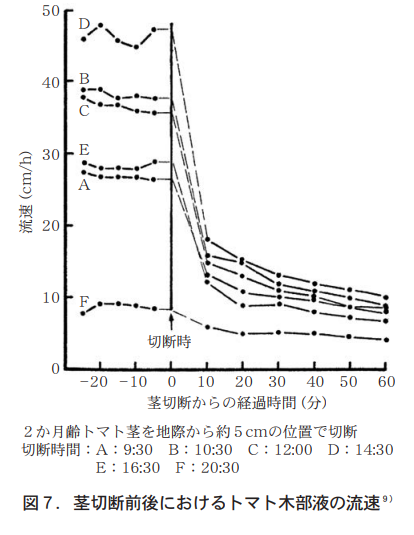

To what extent does stem excision reduce the velocity of xylem fluid? A heat-pulse thermistor was inserted a few centimeters below the site of planned stem excision to measure the xylem flow velocity of 2-month-old tomato plants. After the stem was cut, the flow velocity decreased rapidly, reaching 18 cm/h for the former and 6 cm/h for the latter after 10 minutes, showing a gradual decrease with time (Figure 7).

一般に,根から地上部への水の移動速度は蒸散作用と根圧の強度によって律速される。蒸散の盛んな植物では根圧の影響は極めて小さくほとんど無視できる程度で,しかもその根圧は根から離れるにつれて小さくなり,ついには全く見られなくなるとされる18)。従って,この結果は,地上部10cmの部位における蒸散力と根圧の影響の比率を示すものとして理解される。茎を切断すると蒸散力がなくなるため流速は急激に低下し,その値は日中には切断前の約1/4にもなる。このことから,日中の水の移動にはこの部位で蒸散力が約75%,根圧が約25%の割合で働いているものと推定できる。

この時,いっ泌液の成分濃度はインタクト植物の木部液の成分濃度を反映している必要がある。この点については多くの研究者により議論され,ArmstrongとKirkby1)は茎切断後15分〜60分の濃度が安定しており,インタクト個体の濃度を代表させるのに最も良いとしている。筆者らも茎切除後,15分間毎に1時間いっ泌液を採取し分析したところ,切除後1時間内の成分濃度にほとんど変化が認められないことから,この値はインタクト個体の木部液濃度を反映しているものとした9)。しかし,それでもなお養分の移行を動的に把握するためには,生育中のトマト茎に差し込み木部液の成分濃度を検知するマイクロセンサーの開発等が望まれる。

5. daytime and nighttime xylem secretion and culture medium concentrations

Assuming that water and nutrients are moving from the roots to the ground without retention, the concentration of secretion is equal to the concentration of absorption (n/w). Of course, if we look at these over time, the former is a point analysis and the latter is a linear analysis, so the numerical values rarely coincide, but it is thought that the analytical values of secretion at midnight and noon will not be far from approximating the n/w values at night or in the daytime. It is also a well-known fact that root nutrient water absorption varies with seedling age.

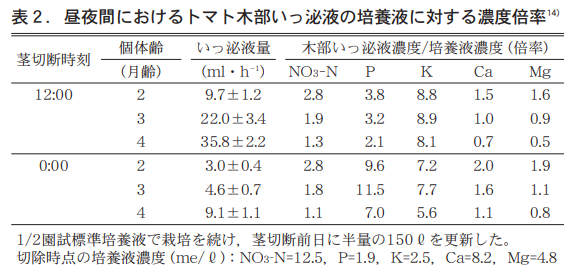

そこで1,2,3月にトマトを播種し園試処方1/2培養液で栽培を続け5月に茎切除し(12:00と0:00)1時間採取のいっ泌液とその時の培養液の分析値から,いっ泌液濃縮係数(XylemSapConcentration Factor (XSCF) を求めた(表2) 。XSCFは,いっ泌液濃度を培養液濃度で除した値で,これはRussel and Shorrocks20)のTranspiration stream concentration factor(TSCF) に準じて筆者が記した名称である9)The following is a list of the most common problems with the "C" in the "C" column.

これを見ると,齢が進み樹の大きくなるほどいっ泌液量は多く,いずれの齢でも12:00は0:00の3〜5倍となる。養分のNO3−N,Ca,Mgは齢が進むにつれてXSCFが低くなる。特に4か月齢のトマトではCaで昼0.7,Mgで昼0.5,夜0.6と1以下となり,いっ泌液濃度は培養液濃度より低くなることが分かる。

In contrast, the XSCF of P was as high as 2.1 during the day and 7.0 at night, even at 4 months of age, and was much higher at night. Conversely, the XSCF of K was 8.1 during the day and 5.6 at night, with daytime values much higher. The extremely high XSCF of K for both day and night may be due to the fact that the concentration of the culture medium at the time of analysis (2.5 me/ℓ) had decreased to 1/3 of the original concentration, as noted at the bottom of Table 2.

As discussed above, the n/w of each component is higher at night when water absorption is low and lower during the day when water absorption is high. In particular, the n/w of P at night is 4 to 5 times higher than that in the daytime, much higher than the values of other components. Why is P absorbed more than other components even at night when water transfer is low? Among the multifaceted physiological functions of P, it may be because P is involved in cell division and proliferation, the formation of nucleic acids and cell membranes, and the production of ATP necessary for respiration, all of which take place constantly during the night, and are required to the same extent as during the day.

一方,Kのn/wは夜間の方が高いにも関わらずXSCFは昼間の方が高い。夜間の養分吸収とその移行にタイムラグが存在するにしても養分の中でKだけがそうなるとは考えにくい。Ben Zioniら2)は,植物におけるKの地上部から根へのフィードバックメカニズムを提唱し,KはNO3−N のカウンターイオンとして働いているとしている。トマトにおいても地上部から根へ移行してきたKが再び地上部へ移行していることが確認され,それは生育条件によっても異なるが,最も高い時で輸送濃度の20%を占めるとされる1, 7)。筆者も木部いっ泌液のK濃度は明け方から上昇することを明らかにしているが(14),これには根に転流してきたKの再転流が関係している可能性が高い。これまで述べてきたように,夜間におけるPの動きと昼間におけるKの動きを32Pと40K(製造するのが極めて困難とされている)で可視化することができれば,それは作物の栽培管理に極めて有用な知見を提供することになる。

6. last but not least - future prospects

植物によるカチオンの吸収のme総和(NH4⁺+K⁺+Ca2⁺+Mg2⁺+Na⁺)がアニオンの吸収の総和(NO3⁻+SO42⁻+H2PO4⁻+Cl⁻)を超えると,植物は根圏へカチオン(H⁺)を排出しなければならず,その結果,細胞内のpHが高くなるのでホメオスタシス(恒常性)を維持するため,取り込まれた過剰のカチオンは有機酸の合成を高めて細胞内のpHの高まりを調整するとされる16)。生物のもつこのような生理機能も「動的平衡」 3)の一例として理解できる。木部液においてもカチオン−アニオンのバランスは維持されているはずで,夜Pと昼KのXSCFに関連するカウンターイオンは何か,根へ再転流して互いにその一端を担っているのか,大変興味ある問題である。

一方,根の水透過性は日中に高く夜間に低い日周変動を示し,これにはアクアポリン発現量が密接にかかわっているとされる。アクアポリン発現量は暗期開始数時間後に最低となり,その後,明期開始に向けて徐々に増加することから,この発現量の日変動はサーカディアンリズムに支配されると考えられている8)。根特異的なアクアポリン遺伝子が明期開始後に急激に発現するが,地上部の湿度を100%近くに保つとアクアポリン遺伝子の発現誘導が見られなかったことから,根における急激なアクアポリンの発現誘導は,サーカディアンリズムに加えて地上部からの蒸散要求が大きく関わっているとされる21)The following is a list of the most common problems with the "C" in the "C" column.

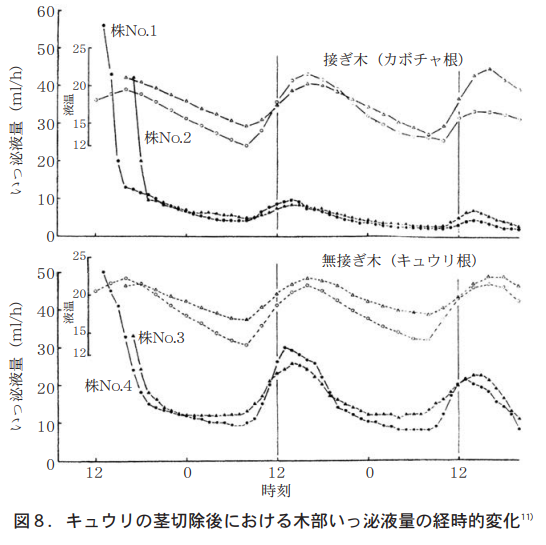

筆者らは,接ぎ木キュウリと自根キュウリについて,木部いっ泌液を48時間にわたり1時間毎フラクションコレクターで受け,いっ泌液量と無機成分を分析したところ,カボチャの根でもキュウリの根でも,いっ泌液量は明らかにサーカディアンリズムを示した。それは午前8時ころから急激に上昇し午後2時にピークとなる。その後,徐々になだらかな曲線をえがいて日出頃に最低となる(図8) 。この時,無機成分のNO3−N濃度は急激に低下し,6時間後には直後の約1/2となるのに対して, P濃度は急激に上昇し6時間後には直後の2倍近くとなった11)。この実験では地上部を除去しているので蒸散の影響は無視でき,正に根そのものの反応(根圧)と理解される。

このサーカディアンリズムにはアクアポリン遺伝子はどうかかわっているのだろうか。イネの根では多くのアクアポリン分子種が明期開始数時間後に遺伝子発現量のピークを迎える日周変動を示し,タンパク量ではさらに2〜3時間後にピークを迎える21)。最近,岡山県のノートルダム女子高校の前田彩花さんは,温度一定の明暗条件におけるアジアイネの吸水の日周変動を詳細に調べ,吸水上昇は明期開始前から顕著にみられ,アクアポリンの転写量は明期開始前後に増加することを明らかにし,吸水が蒸散よりも先に発動する可能性の高いことをJSEC−2019(朝日新聞社などが主催する学生を対象とする学術賞「高校生・高専生科学技術チャレンジ」)で発表している。

木部での水輸送が蒸散力と根圧によることはよく知られているが,根圧による水吸収とアクアポリンの遺伝子発現の関連性については未だ報告はみられない。根の吸水には溶液の浸透圧が関係し,加えて養分吸収の促進あるいは阻害を伴なうので,根の機能解析には水と養分を両極に据える必要がある。さらに根は地上部からのシグナルに応答していることを考えると,上述の重水トレーサーやPETIS技術などを個体における動態解析の手段として駆使し,その成果を高い階層レベルの統合的科学6)へ,とりわけ作物栽培・生産学の領域に応用していくことが重要であると言えよう。

References

1.Armstrong, M. J. and E. A. Kirkby. 1979.

Estimation of potassium recirculation in tomato plants by comparison of rates of potassium and calcium accumulation in the tops with their fluxes in the xylem stream. Plant Physiol. 63: 1143-1148.

2.Ben Zioni, A., Vaddia, Y. and S. H. Lips.1971.

Nitrate uptake by roots as regulated by nitrate reduction products of the shoot. Physiol. Plant. 24: 288-290.

3.福岡伸一.2017.

新版動的平衡.小学館新書.−動的平衡とは何か−.260-263p.

4.今井俊治・岩尾憲三・藤原多見夫.1991.

ブドウの生体情報の測定と解析による土壌水分管理法の指標化.3.

土壌乾燥と茎径並びに果粒肥大の日変化特性.生物環境調節29: 19-26.

5.金井俊輔.2009.

トマトの物質生産に及ぼす環境ストレスの影響と

その生体情報に基づく栄養生理学的解析.広島大学学位論文.115p.

6.菊池卓郎.2009.

新しい統合科学としての園芸科学の確立をめざして.

農業および園芸.84:319-326.

7.Kirkby, E. A., Armstrong, M. J. and J. E. Legett. 1981.

Potassium recirculation in tomato plants in relation to potassium supply.

J. Plant Nurti. 3: 955-966.

8.Lopez, F., Bousser, A., Sissoëff, I., Gaspa M., Lachaise, B., Hoarau, J. and A.

Mahé. Diurnal regulation of water transport and aquaporin gene expression

in maize roots: contribution of PIP2 proteins. Plant Cell Physiol. 44: 1384-1395.

9.桝田正治.1989.

トマトおよびキュウリの真昼と真夜中における木部いっ泌液の無機成分濃度.

園芸学会誌.58: 691-625

10.桝田正治.1992.

トマトの夜間における生育と窒素吸収.

平成3年度科学研究報告書(一般研究C) .課題番号02660033: 3p.

11.Masuda, M. and K, Gomi. 1982.

Diurnal changes of the exudation rate and the mineral concentration

in xylem sap after decapitation of grafted and non-grafted cucumbers.

J. Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 51:293-298.

12.桝田正治・今野裕光.2021.

トマト,メロンの紐栽培における肥料袋の投入箇所と培地の太陽熱消毒について.

農業と科学728: 1-7.

13.桝田正治・野村眞史.1995.

トマトの摘心及び果実除去が根の養分吸収と酸素消費に及ぼす影響.

園芸学会誌.64: 73-78.

14.桝田正治・島田吉裕.1993.

トマト木部いっ泌液における無機成分濃度の日変化およびその濃度に及ぼす光照度と苗齢の影響.

園芸学会誌.61: 839-845.

15.Masuda, M., Tanaka,T. and S. Matsunari.

Uptake of water and minerals during day and night in tomato and cucumber plants.

J. Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 58: 951-957.

16.松本英明.1991.根圏のpHに及ぼす植物の影響.

土壌肥料学会誌.62: 563-572.

17.太田勝己.1996.

ミニトマトにおける裂果発生の機構解明とその制御に関する研究.

京都大学学位論文,52p.

18.Pate, J. S. 1962.

Root-exdation studies on the exchange of 14C-labelled organic

substances between the roots and shoot of the nodulated legume.

Plant and Soil. 17:333 -346.

19.Rudich, J., Rendon-Poblete, E. and A. Abdel-Ilah. 1981.

Use of leaf water potential to determine water stress in field-grown tomato plants.

J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 106:732-736.

20.Russell, R. S. and V. M. Shorrocks. 1959.

The relationship between transpiration and the absorption of inorganic ions by intact plants.

J. Exp. Bot. 10: 301-316.

21.Sakurai-Ishikawa, J., Murai-Hatano, M., Hayashi, H., Ahamed, A., Fukushi, K.

Matsumoto, T. and Y. Kitagawa. 2011.

Transpiration from shoots triggers diurnal changes in root aquaporin expression.

Plant Cell Environ. 34: 1150-1163.

22.Terabayashi, S., Takii, K. and N. Namiki.

Variation in diurnal uptake of water and nutrients by tomato plants

of different growth stages grown in water culture. J.Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 59: 751-755.

23. Tsukamoto, T., Ishii, R., Tanabata, C., Suzui, N., Kawachi, A., Fujimaki, H. and Kusakawa, T. 2020.

Positron-emitting Tracer Imaging System

(PETIS) 法を用いたトマト果実への光合成産物の転流に果実直下の側枝葉が及ぼす影響の評価.

園芸学研究.19: 269-173.

24.山崎肯哉・鈴木芳夫・篠原 温.1976.

そ菜の養液栽培(水耕)に関する研究.

特に培養液管理と見かけの吸収濃度(n/w)について.東教大農紀要. 22: 53-100.

25.Went, F. W. 1944.

Plant growth under controlled conditions (II). Amer. J. Bot. 31:135-150.

土のはなし−第12回

堆肥の効果の現れ方と土の条件

−土の黒さが決め手−

Jcam Agri Co.

北海道支店 技術顧問

松中 照夫

In the previous issue, I reviewed the history of how, in the days before the advent of chemical fertilizers, farmers overcame the difficult problem of supplying nutrients to farmland by devising a material called compost. I also mentioned the difference in the way of farming between the fields in Europe and the rice paddies in Japan, which led to a difference in the way of thinking about compost. Even after the advent of chemical fertilizers, compost is expected to have various effects. However, these various effects do not occur in all soil types without exception. Let us consider what are the conditions of soil that cause differences in the manifestation of these effects.

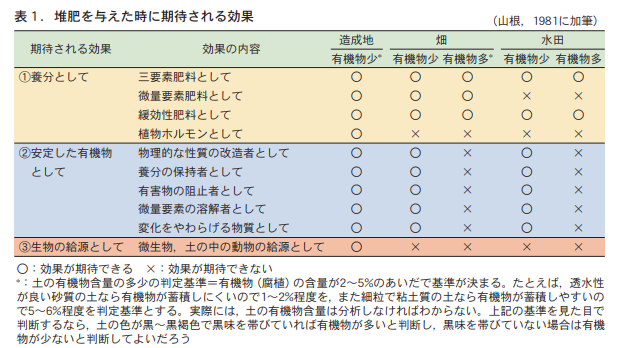

1. expected effects of compost

Compost is expected to have three major effects (Table 1). (1) as a nutrient, (2) as a stable organic matter that is relatively resistant to decomposition, and (3) as a source of living organisms. It is often said that composting will automatically produce all three effects at the same time. This is probably the reason why people think that compost improves the soil. However, these three effects are "expected effects" and do not always appear.

(1) Effect as a nutrient

まずは,養分としての効果である。堆肥を与えることで直接的に期待できる効果は,この効果である。具体的には,①多量要素,とりわけ三要素(窒素,リン,カリウム)の供給源,②微量要素の供給源,③ゆっくりと効果があらわれる肥料(緩効性肥料)としての効果,④植物ホルモンの供給源,などである。これらの効果のうち,土の条件にかかわらず,堆肥を与えることで効果が確実に期待できるのは,①の三要素肥料としての効果である。通常の畑や水田の土で,窒素,リン,カリウムのいずれもが作物生産の制限因子とならないという土は考えにくいからである。また,③緩効性肥料としての働きも,土の条件にかかわらず期待できる。それは,堆肥が土に与えられた後,土の中の動物(トビムシ,ワラジムシ,ミミズなど)や微生物(細菌,放線菌,糸状菌など)などが協力して堆肥を分解し,その分解にともなって堆肥から養分が徐々に放出されるからである。堆肥を連用すれば,累積的で持続的な養分効果も期待できる。

However, the effect of (2) as a trace element fertilizer cannot be expected in paddy fields. This is because trace elements are dissolved in irrigation water in rice paddies, and the amount of trace elements supplied by irrigation water, which is taken up in large quantities during rice cultivation, is large. Even if the compost contains trace elements, the limited amount of trace elements supplied by the compost will not be equal to the natural supply from the irrigation water.

It is not yet well known how effective the plant hormones (4) can actually be in fields and rice paddies with a history of cultivation. However, it is likely to be effective when the surface soil containing organic matter is completely removed and the subsoil containing little organic matter is used as the cropping soil, as is the case in cultivated land.

(2) Effect as stable organic matter

The second expected effect is as stable organic matter. Stable organic matter is organic matter that remains in the soil after being decomposed to some extent by animals and microorganisms, and is relatively difficult to decompose. This becomes the substance known as soil organic matter (humus), which gives the soil its black color.

When compost is incorporated into the soil, the easily decomposable organic matter in the compost is decomposed to produce a nutrient effect. On the other hand, the organic matter that remains in the soil because it is relatively difficult to decompose, together with the organic matter that was already in the soil, will show effects as stable organic matter. These effects include (1) improvement of physical properties of the soil, such as the size and proportion of gaps in the soil (pore distribution), ease of drainage (permeability), water retention (water holding capacity), air permeability (aeration), and ease of cultivation (tillability), (2) increase in nutrient holding capacity, and (3) suppression of toxic substances, for example, when organic matter binds with aluminum When organic matter combines with aluminum, it suppresses the toxic effects of aluminum (chelating action), making it difficult for aluminum to combine with phosphorus.

その結果,リンの養分効果が出やすくなるといった効果,④微量要素は水に溶けにくい形態であることが多い。しかし,有機物が分解されるにともない二酸化炭素(CO2)が放出され,これが水に溶けて炭酸水となって微量要素を溶けやすくする働き,さらに⑤有機物の持つ環境変化をやわらげる作用(緩衝力)などが考えられる。

However, these various expected effects of compost as stable organic matter appear only when the organic matter content of a given soil is less than a certain criterion (ranging from 2 to 5%, depending on the soil), and no effect can be expected if it is higher (Yamane, 1981). This is because in soils with high organic matter content, the physical properties of the soil are less likely to be a limiting factor in crop production, since the soil originally contains more stable organic matter (humus).

(3) Effect as a source of living organisms

三つ目の効果は生物の給源としての効果である。堆肥中には多くの生物(ミミズなどの小動物や微生物など)が生息している。堆肥を与えることは,土の中にこれらの生物を供給することになるので,その供給源としての効果が期待できる。しかし,この効果も堆肥を与える土が通常の土であれば,その土に生息する生物数が,与えられた堆肥に含まれている生物数にくらべて圧倒的に多く,堆肥に土の生物の給源としての直接的な効果を期待しにくい。この効果も造成地のような極度に有機物の少ない土が作土となった場合に限定すべきである。

The effect of compost application on soil organisms is more likely to be cumulative than a one-year effect. However, even in this case, the direct effect of the diversification and increase in the number of organisms on crop growth may vary depending on other soil conditions.

2. the less organic matter in the soil, the more effective compost is.

When we give compost to the soil nowadays, are we just giving it to the soil without any particular reason, just because it is for "soil building"? We need to think carefully about why we are giving compost to the soil and what effect we expect it to have. Depending on soil conditions, compost may or may not have the desired effect. As shown in Table 1, the criterion is whether the soil has more or less organic matter.

The amount of organic matter in the soil can only be determined by strictly analyzing it. To determine the amount of organic matter without analyzing the soil, look at the color of the soil. If the color of the soil is black to dark brown with a black tint, you can judge that there is a lot of organic matter in the soil.

Soils with low organic matter (light black color) can expect diverse effects from compost feeding. For soils with high organic matter (dark black color), we should expect mainly nutrient effects as a slow-release three-element fertilizer.